I grew up reading the Discworld novels of Terry Pratchett, through my teens and probably into my early twenties as well. A prolific writer, averaging two books per year, writing a total of forty one books in a series that combined humor with science fiction and fantasy clichés. As a collective work, it is both absurd and brilliant, on par with Douglas Adams novels in its humor and observation.

The character of Captain Samuel Vimes appeared in 11 of the 41 Discworld novels. A complex character that through the novels, journeyed from being a cynical, world weary, possibly alcoholic police officer, jaded by corruption and injustice, to being a compassionate leader. His experiences shaped him into a more understanding and effective leader but still maintaining that gruff exterior. He taught my younger self about loyalty to friends, a respect for right and wrong, and a desire to do right in spite of the prevailing social order.

He also had some lessons on wealth and inequality that I want to dig deeper into.

“The reason that the rich were so rich, Vimes reasoned, was because they managed to spend less money.”

Terry Pratchett – Men At Arms

The ‘Boots’ Theory of Socio-Economic Unfairness

The “Captain Samuel Vimes ‘Boots’ theory of socioeconomic unfairness” is a satirical observation that highlights the inherent disadvantage faced by individuals with limited financial resources. It suggests that while the rich can afford to purchase higher-quality, longer-lasting items, the poor are often forced to buy cheaper, less durable products that require frequent replacement, ultimately leading to higher overall costs.

“Take boots, for example. A man who could afford fifty dollars had a pair of boots that’d still be keeping his feet dry in ten years’ time, while a poor man who could only afford cheap boots would have spent a hundred dollars on boots in the same time and would still have wet feet“

Terry Pratchett – Men At Arms

His example illustrates the fundamental principle behind the boots theory. While the initial purchase of the higher-quality item may require a larger upfront investment, it ultimately leads to lower overall costs and a greater return on investment over time. However, this advantage is not accessible to individuals who lack the financial resources to make that initial investment.

This is an aspect of the “Poverty Trap“, where individuals are caught in a cycle, draining their limited resources and preventing them from saving or investing for the future. There is a difference between situational poverty (as a result of a specific incident) and generational poverty (cycle that passes from generation to generation) but I will leave that for a later article perhaps.

Being Poor Is Expensive

Much has been written about wealth inequality, thousands of pieces of academic literature, studies, statistical analysis, PhD doctorates. Yet, it still exists. The easy answer is to blame capitalism, as many do. It’s also very easy for the pro-capitalism voice to tell people that they just need to work hard and invest and you can accrue wealth. Neither of those viewpoints have any nuance, nor do they actually make sense in our modern world.

Global income distribution, over the last 200 years since the Industrial Revolution, in inflation adjusted terms, has lifted the majority of the human population out of serfdom and poverty. In 1800, over 80% of the world lived in what we consider extreme poverty today. Fast forward to 2023 and that figure is only 18% of the global population living in poverty. Our modern world is demonstrably better at bringing people out of poverty, but can we keep them there?

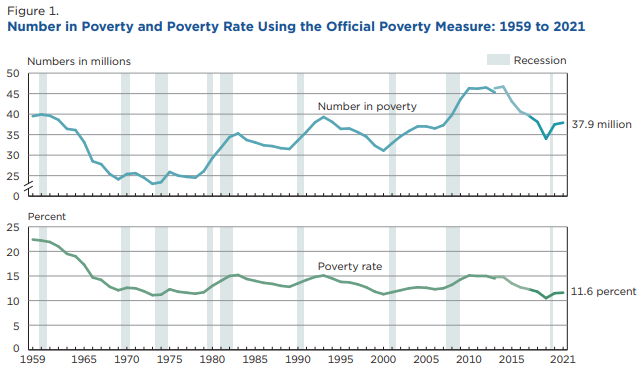

Global wealth metrics aside, what I really want to talk about is how developed Western nations (using the USA as an example) have created a system whereby more and more people each year are unable to escape the poverty trap. In percentage terms they are on par with the mid-1970’s. You can also see from the chart below that each recessionary impulse leads to an acceleration of the trend. This is the wealth destruction of inflationary market cycles, the Boom & Bust, that takes its toll on lower and middle class earners.

Once you are below the poverty line it is very difficult to climb back out. Ironically, you might think that once you are wealthy it is difficult to become poor again, but long term studies show that within three generations, 90% of the wealthy families lose their fortunes to some of the same things that keeps poor people in poverty. For the wealthy it might be investment scams, overspending, extravagance & indulgence, familial infighting and many other reasons. For the poor, it is much more insidious.

At the crux of it, unfortunately, is financial education and a predatory monetary system that punishes those already poor. People with limited financial resources are often targeted by predatory lending practices, pay-day loans, loan sharks, rent-to-own schemes, all of which trap them in a debt cycle. Borrowing to pay off previous debts which creates more debt to the point of default. More staggering perhaps is the cost of poor people on the state and its complete inability to raise them out of poverty through handouts. Over 55 years the US Government has increased welfare handouts from an inflation adjusted $14,895 ($1,612 in 1967) to $32,031 per person in 2022. Spending on welfare has doubled, the percentage of people in poverty remains relatively static, but the numbers in poverty keep increasing.

Follow The Green Rabbit

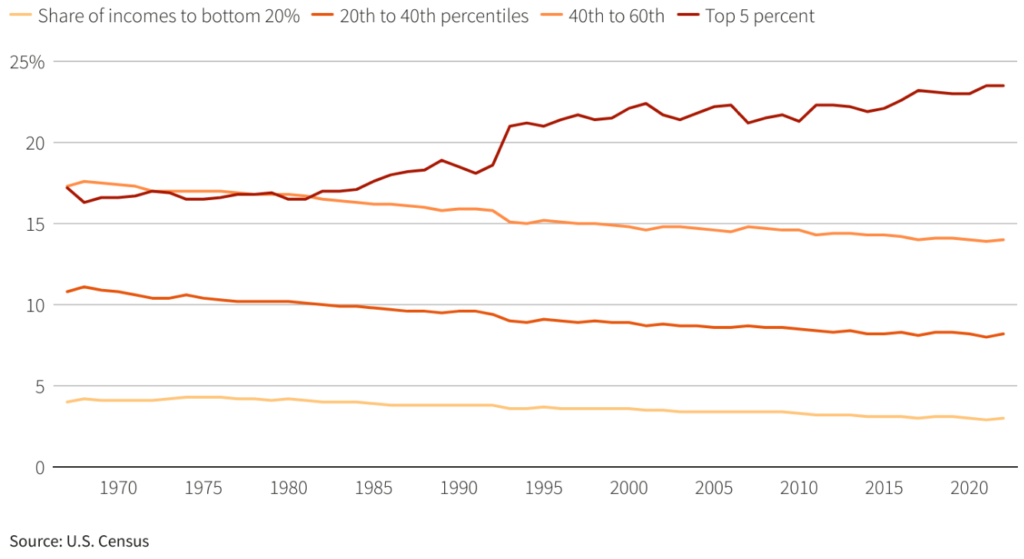

If the money that is flowing down isn’t helping raise people out of poverty, it must be flowing somewhere, right? Well, yes, it’s flowing right back up again. These same predatory financial systems that trap the poorest in society are run by institutions that benefit the wealthier in society. Since the 1980s the share of income has trended upwards, with the top 5% increasing their share of earnings from about 17% to 24% of national earnings, a trend that only increased during the last 3 years during which the poorest lost $3.5 trillion in wealth and the richest gained $3.5 trillion.

Whilst the you would think that the lower to middle class (20th to 60th percentile) would have it better, those with some investable capital, pension & retirement funds, a small portfolio, who spend less than they earn, should be financially better off. In reality, they are suffering the curse of the wage earner. As fiscal drag occurs (taxes rates rising slower than inflation) they find themselves with higher taxes and retaining less of their income. This is true more for those earning an hourly wage or are salaried, compared to the top 5% who earn more income through lower tax means. This fiscal drag happens as Governments spend to excess, in part by having to sustain ever larger numbers of those on the welfare state and running a spending deficit. More to the point, even those in a full time job are having to be subsidised by the state to a minimum standard of living.

Why Doesn’t the Government Do Something?

Realistically, the Government has been doing something for 55 years and it’s bad at it. Worse, the politicians that we vote for are not incentivised to create long term programs that might help. Providing financial support to low-income individuals and families is often more politically palatable than investing in large-scale economic development projects. This is because the benefits of financial support are more immediate and visible, while the benefits of economic development projects may take years to materialize.

This high time preference thinking leads to short term boosts in popularity but a long term net negative to the nation. It also encourages deficit spending, sometimes funded by Quantitative Easing in order to pay for these programs, or attempt to boost an economy. The second order effects of QE can lead to asset bubbles, as investors seek to protect their savings from inflation. It also leads to price rises, which can erode the purchasing power of individuals, particularly those on fixed incomes. When these bubbles burst, it can lead to economic instability and recessions as we see in Fig. 1.

Promoting economic growth and job creation is a complex task that requires careful planning and implementation. It is not always clear which projects will be most effective in creating sustainable jobs and reducing poverty. What we do know, however, is that the current route is innefective and unsustainable.

Conclusion

I’m going to end Part 1 here and pick it up in Part 2. In attempting to address socio-economic inequality we will have to look at the role of financial literacy, individual responsibility, and systemic changes in breaking the cycle of poverty. However when the system is designed to keep the poorest poor, and level down the middle class, it would seem we have a long road ahead of us.

5 thoughts on “Chpt 24.1: Profit Margin”