Captain Sam Vimes’ belief was that people are motivated entirely by self interest. That those with wealth use it as a marker of influence and status, and those who possess great wealth are often able to exert control over others. Something I think most would agree with, and that we do indeed live in a world where money is often used as the measure of a person’s worth.

Milton Friedman counterpointed the idea that self interest is not inherently bad and that every single person does this without realising; “Self-interest is not myopic selfishness. It is whatever it is that interests the participants, whatever they value, whatever goals they pursue”. After all, doesn’t everyone act in their own self interest? Be it moral, spiritual, physical. All of us, at all times, are motivated to make our own lives better or follow a moral imperative.

As this is Part 2, I recommend you read Chpt 24.1: Profit Margin before continuing this article. I will also freely admit my own bias and opinions in places with this article. Take that for what you will. DYOR.

“If a man tells you he is rich, he probably is. If a man tells you he is not rich, you can be sure.”

Sam Vimes, Snuff

Back To The Austrian School

True financial education of how our monetary systems work is anathema to those who benefit most from it. I’m not talking about the infrastructure of the banking system, licenses, trade agreements, currency swaps, bond markets, or even stocks and share markets. I mean the absolute nitty gritty, base layer, level 0 concept of ‘money’. Modern society is so far removed from the money that our grandparents and great grandparents had that it has skewed and distorted our entire way of living.

The money that the previous generations used was backed by the fundamental and immutable rules of physical reality. By that, I mean Gold for the most part, and Silver for a time as well. Gold was money for 5,000 years in one form or another. Money is the means by which humans, outside of a barter economy, transfer value through space (physical distances) and time (maintaining its value). In addition, Gold became the money of choice because it was difficult to produce (requiring labor and capital investment), and thus relatively scarce, and people were willing to accept it in trade for the products of their labor (high salability).

Scarcity is a fundamental concept in Austrian economics. Scarcity arises from the inherent mismatch between human wants and desires, which are infinite, and the resources available to satisfy those wants and desires, which are finite. This scarcity forces individuals to make choices about how to allocate their limited resources in order to maximize their satisfaction. In other words, individuals must decide which goods and services to consume, how much to consume, and when to consume them. These decisions are based on individual preferences and subjective assessments of value.

The supply of gold through recorded history has increased at a rate of 1% to 2% per year. Global economic growth tends to beat this rate over a long period. This means that someone holding money that was either exchangeable for gold (gold backed paper currencies redeemable at a fixed rate) or held physical gold, knew that it would generally appreciate in value of the difference between inflation and economic growth. This understanding that they could retain wealth, represented in a physical object, meant a trend toward low time preference planning. With an amount of economic certainty for the future you can plan a large purchase, establish a savings plan or set out to retire at a specific date.

This also means that people have to make a rational decision over how they satisfy their wants and desires, against their means.

Something From Nothing For War

Under a gold standard a Nation State or a Government is subject to the same law of scarcity that individuals have. It has a spendable amount based on income (from taxation) and debt (from bonds), and it has a desire to accomplish various things in the real world. This ‘coincidence of wants‘ reared its head most often during periods of historical conflict. A state would go to war, spending its reserves as needed to accomplish its goals. If one side ran out of money before either side was victorious the disadvantaged party would quite often sue for peace in order to end the conflict, but at some level of sacrifice.

“I am suing for peace and am ready to agree to any reasonable terms.”

Duke of Burgundy to the King of France, 1443 (Hundred Years War – 1337 to 1453)

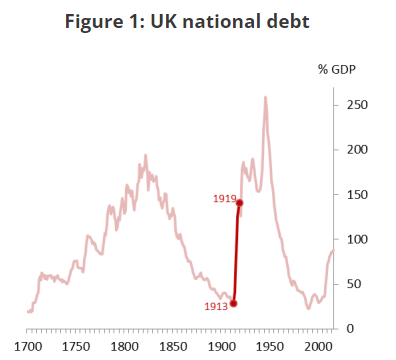

In 2017 some extraordinary documents were found at the Bank of England vaults. In 1914 the British Government was planning to use its commercial and military naval forces to ensure a blockade of the Central Powers, to provide a limited army to support French troops on the Continent and raise the capital to provide arms and supplies for its allies. To do this it would have to borrow an entire years GDP equivalent, from investors, banks, and the public, through 10 year duration war bonds.

Unfortunately for the British Government the population were less enamored with the idea of joining an expensive war on the continent and purchased only 1/3rd of the expected Bond sales. In order to fund their aims, the British government performed two acts of deceit. The first was in using the press to spread fake news that the war bonds were ‘oversubscribed’ and sold well. This skewed public perception over the populations desire to join the war effort (propaganda campaign). Secondly, to cover the shortfall in Bond sales, they used the BoE Chief cashier and his deputy to buy the outstanding war bonds in their name, but held by the Bank of England on its balance sheet disguised as holdings of ‘Other Securities’. This is fraud.

This act not only defrauded the British public of their ability to have a democratic say in whether or not to go to war, it defrauded them of the value of their British pounds, now diluted by new monies created from nothing. This is possibly the first instance of Quantitative Easing. Economic productivity and jobs boomed during this period, as cheap money entered the market, boosting output for the war effort. The increase in the money supply took its toll. Inflation spiked to 25%, but was explained away; blaming supply shocks and shortages due to the war effort.

This is high time preference spending. Borrowing from future generations of the population to fund unwanted government programs and conflict. A pattern we see repeated again and again through the 20th and 21st century. It can be said that had the UK not joined the war it would likely have been shorter and less destructive but allowing for a rise in German power within Europe. This, however, would never have set in motion the sequence of events that allowed for Hitler’s rise to power and the second World War. (In case you weren’t aware, in an effort to win against the overwhelming allied forces, the German bank left the Gold standard, devalued its currency, caused hyperinflation and as a result of their defeat, Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicated and fled the country leaving a power vacuum).

There’s No Money – Only Debt & War

After the end of the first world war, and the costly involvement, the British national debt stood at 128% of GDP and inflation rocketed to 25%. The British economy of the 1920’s was not the ‘roaring twenties’ but a period of depression, deflation and a steady decline in the economic output. Veterans of the war returned to a country with falling employment and economic stagnation. In an attempt to stabilise the economy the British Pound was re-pegged to its pre-war Silver value, but at a level that was too high to be a competitive exporter of goods on the world stage. The USA capitalised on this with a booming manufacturing and production economy.

The UK entered a period of deflationary monetary policy, with higher interest rates to attract savings into the UK. Because US inflation was very low, this meant that the UK was effectively aiming for deflation. The attempt to keep the Pound in an overvalued fixed exchange rate was a key factor in contributing to deflation and lower economic growth. In an attempt to return the UK to fiscal stability, government spending was cut by 75%, and income taxes which had been at ±6% per cent in 1914, stood at ±30% per cent in 1918, with a top rate of ±52% for the wealthiest.

If you read any modern economic history book it will tell you that we left the gold standard because of its volatility in value, creating inflationary and deflationary economic periods. We now understand much better that this reasoning is based on a lie and a fraud. The war and subsequent second order effects of rampant money printing were used as the scapegoat. This inflationary impulse, a credit bubble, peaked and crashed post-war causing a depressive and deflationary period throughout which the UK suffered greatly and lost its position as the global reserve currency. In addition, it opened the flood gates to the creation of a monetary system based on credit creation, expansive debt and the destruction of people’s ability to save in the currency of their country.

“It is no coincidence that the century of total war coincided with the century of central banking.”

Ron Paul

Conclusion

I will end Part 2 here. I didn’t intend on going this far into historical context but felt it was important to understand how credit creation (debt expansion) has deep economic consequences, both in the short, and long term.

One thought on “Chpt 24.2: Profit Margin”