Seigniorage. A word with a long past and an even more sinister present. It originates from the Old French seigneuriage, the ‘right of the lord (seigneur) to mint money’. The seigneurial system was a semi-feudal system of land ownership that originated in France in the 1600’s. Allotted by the king, the seigneurs, or Lords, built large fortified manor houses and administered rural estates. A population of laborers would work the land to support themselves and the lord, initially for in kind payments, and later for monetary returns.

Lords and Kings creating money with their likeness is a practice that dates back thousands of years. By altering the precious metal content in a coin they could finance their activities without having to rely on directly collecting taxes or borrowing. Seigniorage is simply the difference in value between the cost of producing the money, and its face value.

If printing money helped the economy, then counterfeiting should be legal.

Brian Wesbury

Making a Mint

It’s difficult to pinpoint who first implemented seigniorage, as the practice certainly dates back to ancient times. However, it became more formalised in medieval Europe where the sovereigns, or Lords, had exclusive rights to mint coins. When these coins were minted, they would often make them worth more (face value) than the value of the metal they contained. For example, the British pound sterling emerged in around the year 800 from the Carolingian monetary system. The original Tower Pound was introduced by King Henry II and was 349.9g of 92.5% silver and 7.5% of other metals in an alloy. This was subdivided into 240 pennyweights known as the Tealby penny. This ratio meant that for every silver penny that was minted, the king gained 7.5% on the face value as a tax and as revenue for the crown. By 1717 the silver content of the Tower Pound was only 111.4g.

Whilst the kings typically collected land taxes during this period, the use of seigniorage as a form of taxation was an important revenue stream that could not be rejected by the population. It also meant that the kings could alter the level of taxation by changing the percentage of precious metal in the coinage. We can see examples of this in the story of the Roman Republic. In later years, roughly the first century BC, the Roman Republic faced constant financial strain due to wars and political instability. In trying to fund its military expansion and trade, the silver content of its coinage, predominantly the Denarius, dropped precipitously. Initially weighted at 4.5g of nearly pure silver, by the second half of the third century, this was down to just 2% silver content.

In the space of 250 years they debased their currency by 98%, and in return suffered the effects of rampant inflation in prices, wages and lack of trust in the coinage. This debasement of the currency has happened throughout history as empires and kingdoms sought to finance expansion and enterprise by creating money from nothing. Almost without exception, this has ended in hyperinflationary periods and mostly the collapse of the currency in question, if not the empire.

Middling Ground

Seigniorage derived from specie (metal coins) is a tax gathered by reducing the precious metal content versus the face value. In pivoting to paper money an issuer was able to create far more money in circulation than represented by physical assets in a vault. This is known as fractional reserve banking, and what the global economy ran on for a long time. Under the gold standard, banks and governments were able to issue paper currency with convertibility back to a physical commodity. In theory, the transaction back and forth between paper money and gold was without seigniorage. A person could convert one ounce of gold to a government issued gold certificate, keep it for a year, and return it for exactly one ounce of gold.

Issuing more convertible currency than there was gold backing it, or faster than the demand for currency in the economy, always creates the same problem. Inflation of the price of goods, assets and services. Multiple times under the gold standard the currency in circulation far outweighed the gold that was supposedly backing it. This easy credit fueled market bubbles.

When market bubbles popped, due to excessive speculation, and people tried to get their gold back, banks collapsed, businesses failed, and the economy experienced depressive or deflationary periods as people hoarded their gold. This was not a problem of the gold standard, but of fractional reserve lending, and it happened frequently in the early years of the USA (there were eight market “panics” between 1819 and 1907). This boom and bust cycle was often blamed on the gold standard, but in reality it was the fractional reserve lending practices.

Paper money was recorded in usage as early as Kublai Khan in the 13th century when he issued Jiaochao (Chinese: 交钞) banknotes manufactured from the bark of the mulberry tree. Marco Polo travelled to China and marveled at the use of paper money; “The people of China do not do business for dinars and dirhams. In their country all the gold and silver they acquire they melt down into ingots, as we have said. They buy and sell with pieces of paper the size of the palm of the hand which are stamped with the Sultan’s stamp“.

This use of paper money was forced on the population at the time and any other form of money (gold, silver) was illegal under punishment of death. As is typical, and in order to finance war, Kublai Khan printed more of the paper money than the economy could handle. Leading to hyperinflation and rejection of the money as a medium of exchange.

Factoid: The terminology has changed over the years, what used to be known as a panic, became a crash, a recession, a slide, a crisis, a sell-off, a downturn or a bear market.

Seigneur Money Bags

Modern money supply, and seigniorage derived from paper bank notes is more indirect. The machinations of the central banks and the banking system, is complex and interwoven, and has origins dating back to medieval times. The in-specie convertibility of our paper currency has been completely eliminated, and although our central banks hold gold as an asset, it is no longer considered ‘money’. The supply of currency in an economy is no longer directly controlled by the central banks as a function of printing physical notes or coins. Indeed, only about 10% of the global money supply is physical cash. Instead, the amount of money available is a reflection of the central banking interest rates, and people’s willingness to take on debt.

That doesn’t mean that our modern banking system doesn’t benefit from seigniorage. On the Bank of England website it states clearly that “while we only spend a few pence to print each note, banks buy them from us at their face value“. This amounts to hundreds of millions each year, most of which is transferred to the UK government Treasury. Commercial banks have to estimate the amount of physical currency they will require, based on historical cash usage, and use their own profits to buy the paper currency.

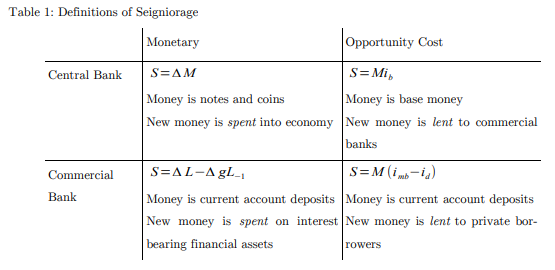

The concept of monetary seigniorage doesn’t necessarily apply to modern banking, even if the central banks, as sole issuers of fiat currency are profiting from it. The monetarism of Milton Friedman is a classic reference point in the literature on seigniorage, which is based on the commodity theory of money.

It has become common to regard inflation produced by the issue of fiat money as a tax on cash balances.

(Friedman 1971

Milton argued that any creation of government money in excess of economic growth led to inflation, with inflation always and everywhere being a monetary phenomenon. He considered seigniorage a form of taxation for anyone holding a cash balance. This has become a complicated equation. Keynesian economists would say that there is a trade off to be made between inflation, growth and seigniorage. The question being, how much, or rather how little money should the central bank issue in order to balance its interests in supporting the government, ensuring economic stability and growth of the economy. But a dollar created, does not a dollar earn in many cases, and the ratio is decreasing over time.

Instead of creating new monetary supply through cash creation, the central banks will increase or decrease new supply through the assets that it holds on its balance sheet. Increasing its holdings of government bonds, loans to banks and other institutions allows those institutions to issue more credit to customers. The same is true in reverse, to reduce the amount of money in circulation it will reduce those same holdings, increasing the cost of credit for consumers and businesses. This is critical to understanding our modern world as a debt or credit based economy, rather than one built on money as we used to understand it.

In theory, states cannot circumvent the separation between government and central banks by letting the central bank purchase government bonds directly with newly created money. Instead, it must purchase them on the open market, competing against other market buyers and sellers, and accepting the fluctuations in bond prices as a result. The exception to this would be when central banks perform Yield Curve Control in order to manipulate the interest rates at a certain level. Something that the Japanese central bank has been doing for 20 years (and the USA did in the post-WWII era) in an attempt to maintain capped borrowing rates for the government so that debt repayments don’t spiral out of control.

Conclusion

I’m not sure if there is a simple way to conclude this discussion. It is undeniable that an increase in the monetary supply, above the liquid demands of an economy is detrimental to anyone who holds any portion of wealth in a cash balance. This is taxation without representation. The central bank policy of maintaining the illusion of growth against an inflationary currency appears to be running out of track. Those with financial knowledge store wealth in assets, those on fixed incomes or are wage earners, lose out to the compounding effects of inflation. The creation of new money appears to be on an unsustainable and exponential path upwards.

But the idea that this is due to central bank money creation is partly incorrect. Yes, there is central bank seigniorage. However it is the commercial banks that create the majority of new money through credit. The creation of money by commercial banks involves two parties. We have the money user, who is willing to accept the debt of the bank in return for taking out a loan. This borrower represents a risk to the bank and must be deemed creditworthy, so the bank will judge this person based on risk and charge interest or perhaps demand collateral.

We are, in some ways, our own worst enemies. We complain about inflation and the increase in the cost of living or buying a house, without realising that we are part of the problem every time we accept credit.

And a person who relies on debt to live, will never break even.

Further Reading:

The Medieval Origins of the Financial Revolution – John H. Munro

The Invention of Money – John Lanchester

Seigniorage in the United States – Manfred JM Neuman – St. Louis Fed

Seigniorage in the 21st Century – Copenhagen Business School

Central Bank Independence and Central Bank Functions – Mr. Mark Swinburne

One thought on “Chpt 37: Break Even”