In 2008 I travelled to Japan with friends and spent time in Kyoto and Tokyo. This was an eye-opening trip for me, someone who had never travelled to a country that didn’t use the Latin Alphabet, bearing in mind that about 50% of countries globally use this as the basis for their written language, and attempting to navigate a country without signage in English was a challenge for us. We were truly Gaijin. This was the first time that I felt like a stranger in a strange land. In the backdrop of this visit was the ongoing Global Financial Crisis, which I was naively unaware of, and the continued economic issues in Japan, which I was very unaware of. I don’t look back on this trip with a view that the country was in decline, but 15 years later we are seeing signs of cracks showing in the once great state of Japan.

She gave birth to a son, and he called his name Gershom, for he said, ‘I have been a sojourner in a foreign land.’

Exodus 2:22

Sedai-Kan Fuwa (世代間不和)

Sedai-Kan Fuwa can be roughly translated as ‘Intergenerational Discord’. This could be something as simple as changing cultural values, changes in fashions, or just the progress of the use of technology between different generations. Creating a clash between how it was, and how it is. However, I think the phrase portrays a deeper malaise, the shift in the realisation that the generations prior to ours lived in a very different time and that the struggles of young people today, especially financially, are much greater than before.

Japan is widely recognised for its rich cultural heritage, technological innovations and resilient spirit, it captivates many and even today, draws people to it in fascination with its art, architecture, history, technology and food. Whilst there are various ethnic groups within Japan itself (Ainu, Ryukyuan, Burakumin) Japan is predominantly ethnically homogenous with about 98% of the population ethnically Japanese. There are not many other countries that display this level of homogeneity in their population, Iceland, Finland, and North and South Korea as some other examples that seem to maintain that level due to environmental or cultural barriers to foreigners.

Decades Lost to Economics (失われた30年)

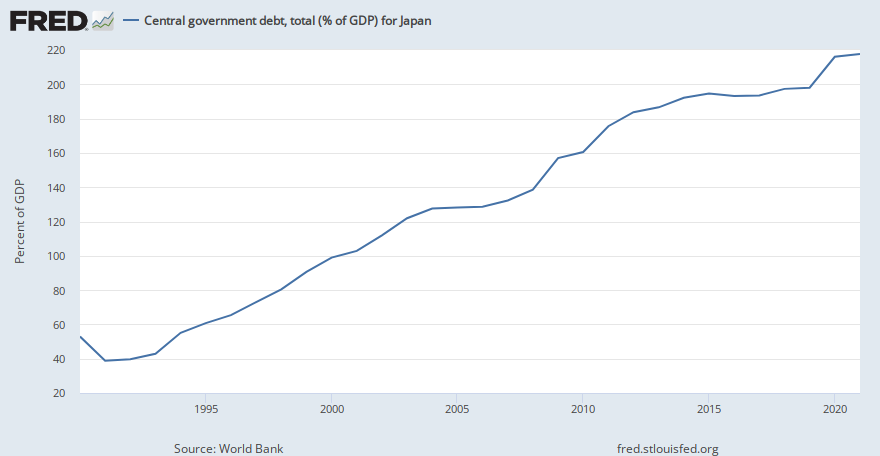

To understand the economic challenges Japan faces today, we must first comprehend the concept of “Japan’s Lost Decades.” It is a term that encapsulates the country’s prolonged economic stagnation, which began in the early 1990s and continues to cast its shadow over the nation. The roots of this stagnation can be traced back to the burst of asset price bubbles, primarily the real estate bubble. The implosion of these bubbles brought about a seismic shift in the Japanese economy, leading to financial instability and a protracted period of sluggish growth. The consequences of this economic downturn have been profound and far-reaching, shaping the experiences of multiple generations.

A defining characteristic of Japan’s economic landscape during these lost decades has been deflation. Deflation, the sustained decrease in the general price level of goods and services, has cast a long shadow over the Japanese economy. The nation has grappled with deflation for a considerable period, leading to what experts have termed the “deflationary mindset.” In this mindset, consumers anticipate that prices will fall further, leading them to delay purchases, thereby hampering economic growth.

Deflation’s impact extends beyond consumer behaviour; it also affects wages. In a deflationary environment, employers may hesitate to raise wages, leading to wage stagnation. This wage stagnation, in turn, results in reduced consumer spending, creating a vicious cycle of economic contraction. Japan’s response to deflation has involved monetary policy measures, including negative interest rates and quantitative easing, enacted by the Bank of Japan to stimulate inflation and economic growth.

We Ain’t Getting Any Younger (若返らない)

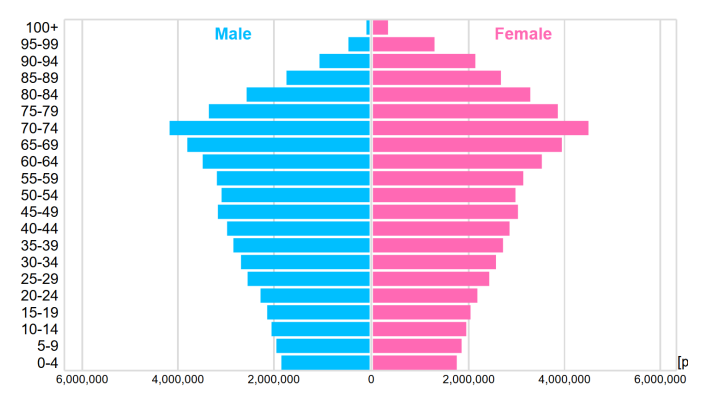

Japan’s demographic landscape is another critical aspect of its economic challenges. The nation is experiencing a rapid ageing of its population, a trend that has profound consequences for its economic dynamics. This demographic shift has resulted from a combination of factors, including increased life expectancy and declining birth rates. As a result, Japan has one of the most rapidly ageing populations in the world.

The ageing population has a multifaceted impact on Japan’s economy. First and foremost, it has significant implications for the labour force. As more individuals retire and fewer young people enter the workforce, there is increasing pressure on the nation’s social welfare systems and healthcare infrastructure. These systems must adapt to accommodate the needs of an older population, and this adaptation has substantial economic costs.

Moreover, an older population influences consumer behaviour. Older individuals tend to spend less on consumer goods and more on healthcare and retirement savings. This shift in consumer spending patterns can have repercussions for various sectors of the economy, including retail, healthcare, and social services.

This demographic stagnation is so profound that in March 2023 the country’s prime minister, Fumio Kishida, said “Japan is standing on the verge of whether we can continue to function as a society. Focusing attention on policies regarding children and child-rearing is an issue that cannot wait and cannot be postponed.”

By 2045 it is expected that the demographic curve will be dominated by those of retirement age and older.

No Growth, Only Debt (借金だけ)

Japan’s economic challenges extend to its government debt levels, which are among the highest in the world relative to its GDP. The nation’s high government debt-to-GDP ratio raises concerns about the sustainability of its fiscal policy. Managing such a significant debt burden poses substantial challenges.

One of the main issues is the potential risk associated with a high level of government debt. The larger the debt, the more significant the risk of financial instability and the potential for debt crises. Additionally, high levels of government debt can limit a nation’s fiscal flexibility, restricting the ability to respond to economic shocks effectively. This situation is particularly concerning in the context of Japan’s economic challenges.

The economic challenges Japan faces, including its lost decades, deflation, ageing population, and high government debt levels, are inextricably interrelated. Each factor amplifies the impact of the others, creating a complex web of economic challenges. The prolonged economic stagnation, for example, exacerbates deflationary pressures, while the ageing population places further strain on social welfare systems and healthcare services.

Monetary policy measures, such as negative interest rates and quantitative easing, have aimed to combat deflation and stimulate economic growth. The government has also implemented fiscal policies to support the economy, including infrastructure investment and stimulus programs. While these policies have had some positive effects, they also face limitations. The impact of monetary policy tools can wane over time, and there are concerns about the sustainability of fiscal policies, given the high level of government debt.

Conclusion

The future of Japan’s economy remains uncertain. The nation continues to grapple with generational disillusionment, economic challenges, and a complex interplay of societal factors. To navigate this challenging landscape successfully, Japan must consider several possible scenarios and strategies.

One scenario involves pursuing structural reforms to boost productivity and economic growth. Encouraging innovation, entrepreneurship, and a more flexible labour market could help revitalize the economy. Additionally, Japan could explore policies that promote higher birth rates and increased immigration to counter the effects of an ageing population.

Another strategy might involve further fiscal and monetary policy adjustments to combat deflation and stimulate inflation. The real risk, however, is that before being able to stabilise the economy they enter a death spiral of debt. In attempting to create inflation and stimulate the economy, the debt levels become so pronounced that they risk hyperinflation or rather a massive and sustained devaluation of the Yen.

Japan, and to be honest, most of the debt-laden global economies, are fast approaching a point where they will be left with only two options, default on their debts, or continue to debase. The default option (a debt jubilee) is the biblical option, literally, and debasement is the current route; leading to hyperinflation and economic collapse.

No wonder we have so much Sedai-Kan Fuwa.

One thought on “Chpt 20: I Blame The Parents”