Word spreads fast when there’s easy money to be made. Something that was apparent in the taverns and public houses of London in the 1700’s. News filtering down from Exchange Alley, through newsletters and pamphlets, gossip, rumors, tales of supposed riches and opportunity. Whispered stories of ordinary people becoming overnight millionaires fueling speculation and encouraging investment, even from those with little financial knowledge or means.

There have been many turning points in financial history, The Mississippi Bubble, Tulip Mania, the Great Crash of ’29, but perhaps none so evocative as the rise and fall of the South Sea Company. It was certainly the catalyst for one of the most dramatic and memorable financial meltdowns of the 18th century.

“Millions of bubbles bouncing in the air, / Each bubble a projector, and a liar.”

Alexander Pope (1720)

In The Company of Hollow Blades

Behind the rise and fall of the South Sea Company lies a man called John Blunt and the Hollow Sword Blades Company. In 1691 the Nine Years’ War between England and France interrupted the importation of hollow ground swords. A hollow grind is characteristic of a straight razer and produces a very sharp, but weak edged blade, prized for its lightness and speed. These had become popular in Britain due to their sleek and elegant lines, a particularly unique and sophisticated appearance, and as a status symbol for the owners. A business opportunity was seen in arranging for Huguenot metalworkers to move to Britain and for the Hollow Sword Blades Company to obtain a monopoly on their production. An official charter gave them power to seize imported foreign hollow swords, and produce their own, on condition that they lent the Government £50,000 (£10,288,704 adjusted for inflation).

The company moved to London and was sold in 1703 to John Blunt. Various financial shenanigans ensued, involving land grants, British government debt and accounting trickery. As a company, they took full advantage of buying discounted British army debt before it was available to trade publicly, and then sold them for full value. It also branched out into providing mortgages for buyers of Irish land, accepting cash deposits and issuing its own notes, bringing upon it the focus of the Bank of England. The BoE advised the treasury that their own monopoly to act as a bank was being infringed, but they took no action, realising that it had a good deal that it did not wish to spoil. After all, someone has to buy the debt to fund the treasury! This all came to an end with the renewal of the Bank of England charter in 1710 setting the BoE as sole issuers of British currency.

Interesting factoid: One of the swordsmiths from the Hollow Swords Blade Company continued to make blades. Founding a company that was subsequently bought by Wilkinson Sword who continue to make razors today.

The Debt Equity Infrastructure

Britain was heavily engaged in the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714) and as a result it needed to raise capital to continue funding it. In February 1710 it announced a lottery, officially known as the Annuity Loan, in order to tap into public funds beyond traditional taxes and appeal to persons of a gambling spirit, tempted by the potential for high returns. This was a turning point in financial history as it was the first lottery authorised by a dedicated Act of Parliament, managed by the Bank of England, and offered prizes in the form of annuities which guaranteed winners a steady income stream.

Interesting factoid: A similar scheme still runs today within the UK, introduced in 1956 and known as Premium Bonds. No interest is paid out but the owners of the Bonds have a chance at winning lump sum amounts. No guaranteed returns for lending your money to the British Government in this fashion.

In September 1710, John Blunt and Robert Harley, formed the South Sea Company using the framework for a joint-stock company originating with the Hollow Sword Blades Company. Although their primary business was shipping, hence the name, their true intention was simple; to leverage Government debt to issue equity in their own company, also known as a “debt-equity conversion”. This was the foundation of their initial success. To begin with they focused on consolidating smaller annuities after securing parliamentary approval for the conversion. They would agree a price slightly above the initial cost, determine the interest rate the company would pay on the converted debt, typically lower than the original annuity rate (e.g., 5% instead of 6%), then claim the difference in interest payments from the Government.

Then the company offered its own stock to annuity holders in exchange for their holdings. This essentially meant people swapping government debt for ownership in a private company. They could accept the stock swap directly, becoming shareholders who would benefit from an increase in share price along with dividends (from the Government interest payments).

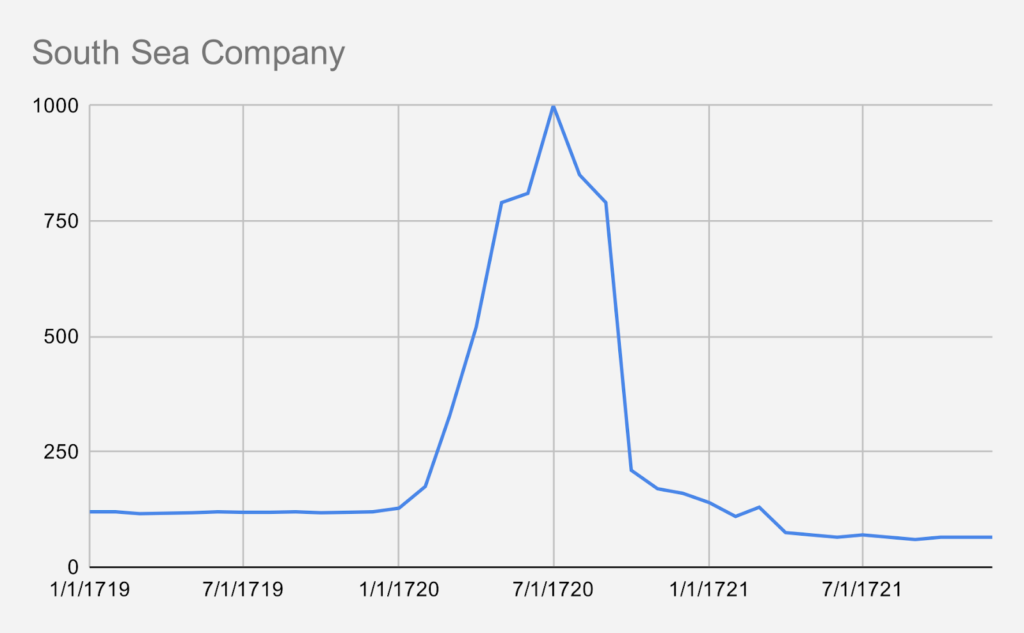

The South Sea Company also raised additional capital by selling shares through public subscription rounds. With an increasing share price and regular dividends they were in high demand. This allowed them to purchase more debt from the Government and as a result they became the primary creditor, receiving regular interest payments from the Treasury. This, along with any profits from their actual shipping company, was paid out to investors through dividends. Between 1718 and 1720 the share price for the South Sea Company rose from £100 to £1,000.

The actual business of the South Sea Company was rather limited and ultimately disappointing. The potential rewards for being involved in shipping and trade were high, but the risks could also be devastating. The main threats were always the unforgiving nature of the Southern Seas, outbreaks of disease due to cramped and unsanitary conditions, and technical failures of the vessels themselves. This was also a period of war and political instability, pirates, privateers and the underlying threat of mutiny and rebellion from the crews.

They had the opportunity to revolutionise trade with South America and beyond, but their ambitions far outweighed their capabilities and ultimately led them to their downfall when profits didn’t materialise. That, alongside mounting debt from lavish expansion plans and speculative ventures contributed to the public disillusionment.

Pop!

In 1720 they peaked. In the January, the South Sea Company surpassed the market value of the Bank of England. In the March, Parliament debated granting the company further monopolies due to its perceived success. Despite their already existing monopoly of the slave trade to Spanish America (Asiento de Negros) they failed to realise enough profits to continue operating. The rise in share value, fueled by hype, speculation and the lure of easy returns pushed the stock price to unsustainable levels. By August, doubts were emerging over the company’s finances, and the ability to deliver on its promises. By the September of that year, the panic selling begins, and the stock crashes.

“I am in the greatest distress about my money that ever I was in my life. I have lost 2000 pounds, and am not worth a groat.”

Jonathan Swift (1720)

As the stock price crashed, losing 90% of its value in mere months, it wiped out the fortunes of countless investors, from wealthy aristocrats to ordinary citizens. Banks and financial institutions who had invested in the South Sea Company were exposed to these losses, leading to credit crunches and an unwillingness to lend. This froze economic activity as businesses struggled to access capital. The government, also heavily tied to the South Sea Company due to the debt conversion scheme, faced public outcry and accusations of mismanagement. Ultimately this eroded trust in the financial system and weakened the governments authority.

As with any market crash, this bursting bubble shattered public confidence in the financial market. It instilled a sense of fear and skepticism towards speculation and risk-taking, hindering future investment and economic growth. It also left behind it a trail of debt for investors and institutions, a period of deflation, with falling wages and price, further squeezing the economy.

Lessons Unlearned

It is said that history doesn’t often repeat, but it does rhyme. Between the 17th century and current day we experience a market crash of varying severity about once a generation. How short our memories are, and how quick we return to the same impulsive behaviors. Human beings have a remarkable ability to forget the mistakes of the past. Focusing more on the present and the future, combining our ability to rationalise past behaviors and our natural desire to avoid feeling guilty or ashamed for previous errors

People are more likely to remember positive events than negative events, that which rewards over that which has connotations of pain and negative emotions. People forget about the past all the time, it can be a healthy way to cope with past mistakes, but can also prevent us from learning them.

“The bubbles are all broken, and the air is full of projects and stocks.”

Daniel Defoe (1720)

A study by Robert Shiller, a Nobel Prize-winning economist, analyzed 23 stock market bubbles and crashes from 1637 to 2000 and found that the average time between bubbles was 7.4 years. Another study by Credit Suisse Research looked at 23 bubbles and crashes from 1870 to 2011 and found an average time of 9.7 years. Some bubbles, like the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s, are characterized by rapid price increases and subsequent sharp declines, while others, like the Japanese asset bubble (Chpt. 20) of the late 1980s, experience a gradual erosion of asset values over an extended period. But that doesn’t change the economic impacts of a market bubble.

Conclusion

“Men, it seems, are in greater danger from over-confidence than from over-caution.”

Charles Mackay (Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds)

The question that needs to be asked, is have we learned from this cycle of bubbles and bursts? I think the answer is no. Because each time this occurs, no matter how frequent or how dramatic the lessons from the past, the market participants are different each time.

In both the current financial climate and the South Sea bubble we had overleveraged markets. Investors and institutions taking on ever more debt, fueling speculation and inflating asset prices. In the 1700’s there were fewer regulations in place compared to today, yet that doesn’t seem to affect human nature and the willingness to play a game of chance, to win and lose fortunes, to repeat history and get caught up in the fervor.

Ultimately, whether we’ve truly learned from history remains to be seen. Every generation appears to reach the point at which it kisses the blade and takes a gamble.

Recommended further reading: Chpt 24.1: Profit Margin (3 parts)

Interesting read

Thank you