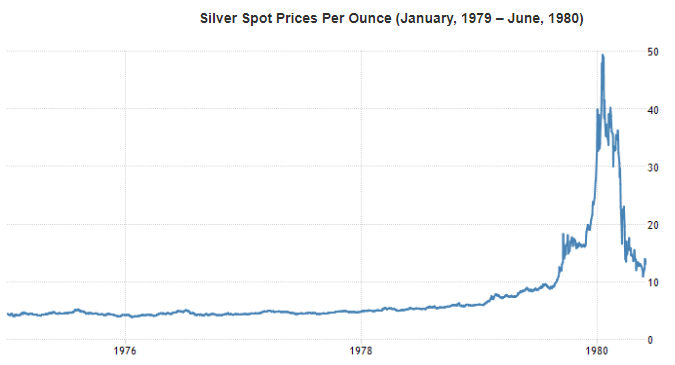

March 27th, 1980. Known amongst commodity traders as ‘Silver Thursday‘. It was described in Harpers Magazine as “the first great panic since October 1929.” In the words of then Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) chief James Stone, it had threatened to punch a hole in the “financial fabric of the United States” like nothing had in decades. Over the course of a few short years in the late 70’s, the spot market price of silver rose from around $6 an ounce, to $50 an ounce, before crashing by 80% in the March of 1980.

The story behind Silver Thursday is as entertaining as it is intriguing. It starts with a poker game in east Texas and ends with three brothers owning two thirds of all the privately held silver on Earth. Eccentric southern yokels, white collar crooks in the same vein as Charles Ponzi or Bernie Madoff, or just victims of overzealous regulators and vindictive insiders.

The jury is still out.

From Texas Tea to Soy & Silver

H. L. Hunt, or more formally, Haroldson Lafayette Hunt Jr., was a Texan oil tycoon born in 1889. According to legend he bought the rights to what became one of the worlds largest oil deposits in East Texas through his winnings in poker games. Whether that is true or not remains shrouded in mystery, but he certainly became prosperous because of it. He didn’t just stick to oil, he diversified into publishing, cosmetics, pecan farming, and health food producers. At the time of his death in 1974 he was one of the wealthiest men in the world with a fortune of $2-3 billion USD.

“In terms of extraordinary, independent wealth, there is only one man—H. L. Hunt.”

J. Paul Getty

Hunt fathered fifteen children by three wives, but this tale involves just three of them; Nelson, William and Lamar. The lifestyles of Hunt’s children was financed by trusts, but they also took on risky investments in oil, real estate, and a host of commodities including sugar beets, soybeans and before long, silver. To understand the motivations for their Silver investment we have to look at the state of the world in the 70’s through the lens of money and oil.

William and Nelson were heavily involved in the oil industry, both in the USA and abroad. Nelson Hunt was a major force in the discovery and development of the Libyan oil fields. From their discovery in 1959 and the subsequent income, it turned one of the worlds poorest nations into an established and extremely wealthy state under King Idris.

The 1970’s was not kind to the US dollar. Years of wartime spending and unresponsive monetary policy had driven inflation upwards through the 1960’s and early 1970’s. In October 1973, war broke out in the Middle East and an oil embargo was declared against the United States. In the process, Muammar Gaddafi nationalised the oil fields that Nelson Hunt had helped develop. A staggering loss to his wealth and influence.

During the same time period the global monetary system underwent a historic transformation. In 1971, then President Nixon, responded to inflationary pressures by suspending the convertibility of the US Dollar to gold (Nixon Shock). For the first time in modern history the paper dollar did not represent some fixed amount of tangible, precious metal sat in a vault.

Like a Cornered Market

The Hunts, who, at the heart of it, were commodity traders, blamed the US governments spending for the high inflation. They held grave reservations about the viability of fiat currency. The perceived stability of precious metal offered a financial safe harbor, and whilst trading gold in the early seventies was illegal under the Gold Reserve Act, you could still trade in the next best thing, silver.

The price of silver in the 1970’s was already on the rise before the Hunts got involved. Not only were other investors fleeing to bullion in light of the inflationary pressures, it was also in demand as part of the growth in consumer photography. New production from mining activities were struggling to keep up with demand. In 1973 the Hunts bought over 35 million ounces of Silver, shipping most of it to Switzerland in specifically designed airplanes and guarded by heavily armed Texas ranch hands. Even at this time, the size of the purchase was enough to move the global silver markets.

In 1977, the Hunts attempted, and were successful, in trading Soybean futures to make tens of millions of dollars. A futures contract is an agreement to buy or sell some quantity of a commodity at an agreed upon price at a later date. It is mostly used to hedge price volatility and as a de facto insurance contract. They can also be used to gamble on price fluctuations. When the Hunts decided to long into Soybean futures, they went very very long. That year, they collectively purchased the rights to buy one third of the entire autumn Soybean harvest of the United States.

When the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) found out about the size of the purchase they declared that the Hunt’s “excessive holdings threaten disruption of the market and could cause serious injury to the American public“. They fined them $500,000.

Back to the Silver

Not put off by the regulators fine, the Hunts looked back to the silver markets. By the autumn of 1979 Nelson and William had accumulated 21 million ounces of physical silver bullion and held even larger positions in the silver futures market. Nelson was long on 45 million ounces and William held contracts for a further 20 million. Their younger brother Lamar reportedly held a more modest position.

By the new year, every dollar increase in the price of silver netted the Hunts $100 million in paper gains. But unlike most commodity futures traders, who took their profits in dollars, the Hunts were taking physical delivery. Again, as in 1973, they arranged to have this silver flown to Switzerland and inadvertently created a shortage for industrial use. This made the industrialists very unhappy. From a spot price of $6 in 1979 it had shot up to $50.42 in January 1980. Film companies like Kodak saw costs go through the roof, and British film company, Ilford, actually had to lay off employees.

“We think it is unconscionable for anyone to hoard several billion, yes billion, dollars’ worth of silver and thus drive the price up so high that others must pay artificially high prices for articles made of silver”

Tiffany & Co.

Traditional traders who were caught out in the price increase complained to the regulators and even the New York jewelry house Tiffany & Co. took out full page adverts in the New York Times slamming the brothers for their market actions. They were right to be outraged, by the January the brothers controlled 69% of all the silver futures contracts traded on the Commodity Exchange (COMEX).

Margin Call

At the end of 1979 the brothers had successfully engineered such a genuine shortage of silver that the rampant speculation, and profits, triggered the COMEX to adopt “Silver Rule 7”. This placed heavy restrictions on the purchase of commodities on margin, something the brothers had been doing heavily to finance their futures positions. This happened on the 7th of January 1980, but it wasn’t enough according to the Chicago Board of Trade exchange who suspended the issue of any new silver futures contracts on January 21st. Traders from this point would only be allowed to close out their current positions.

For the Hunts, this meant trouble. Of the $6.6 billion worth of Silver they held at the top of the market, only $1 billion of their own money had been spent. The remainder had been borrowed from over 20 separate banks and brokerage houses. As the futures contracts wound down, and speculation dampened, so did the price. As the price dipped the brothers were issued margin calls to cover collateral on their debts. The various banks and brokerages were recognising the tenuous financial position the Hunts were in. Unable to sell their silver, the brothers borrowed more to continue to fund their contracts.

It all came to a head on March 25th. One of the Hunts biggest backers, the Bache Group, asked for $100 million more in collateral. The brothers were out of cash, and the group refused to take their silver in its place. With the Hunts defaulting on their loans, the Bache Group began unloading silver on the markets in an attempt to recoup their loss.

On March 27th, Silver Thursday, the silver futures markets dropped by a third to just $10.80, an 80% drop in value from the peak of the market.

The Aftermath

As a result of their actions in the silver markets, and following the oil bust in the early 1980’s, the brothers once historic fortune was reduced to relative pennies. Nelson, who was once worth $16 billion left bankruptcy court in 1988 with a mere $10 million to his name. The resulting default also dragged their lenders into bankruptcy, and with them a good chunk of the domestic financial system. Over twenty individual institutions had extended over a billion dollars in credit and the resulting default and collapse of silver prices left sizeable holes in balance sheets across Wall Street.

Despite the financial chaos, being dragged in front of congressional hearings, and a $130 million fine against them for conspiring to corner the silver market, there is still some disagreement on motive. Although they clearly amassed an incredible amount of physical silver and silver futures contracts, it is impossible to prove that they were definitively manipulating the markets.

Nelson himself felt hard done by and that the whole affair could be attributed to the political motives of COMEX insiders and regulators who had been played by a couple of southern yokels. Perhaps as some noted, they just had no idea what they were doing.

“They’re terribly unsophisticated,”

“They make all the mistakes most other people make,”

“Do you think there’s any possibility that the Hunts are just having fun, just horsing around?”

Conclusion

Regardless of people’s opinion of them, the regulator considered their decision to accept delivery of physical silver, rather than cash, was a deliberate attempt to corner the market. Removing the bullion from supply, and artificially inflating the price. Real traders would obviously only want to make money on trades, rather than holding physical bullion. Some have argued that their unsophisticated trading was consistent with the symptoms of having too much money, too little sense, and an irrational fixation of shiny metal.

Either way, it was legally unacceptable behaviour.

Further reading: US SEC The Silver Crisis of 1980

You may also enjoy Chpt 27: Kiss the Blade about the South Sea Company market bubble